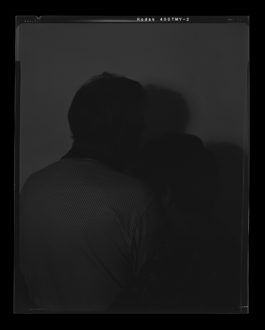

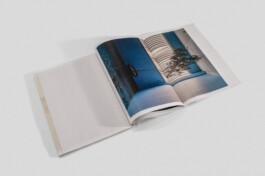

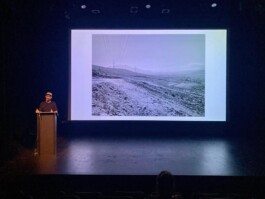

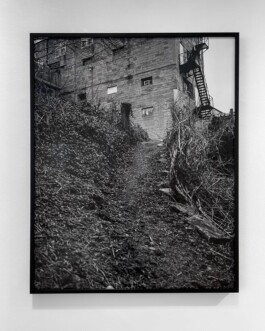

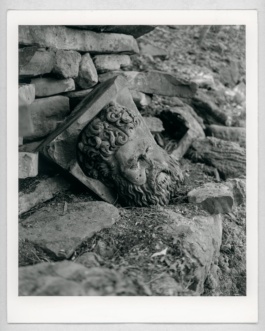

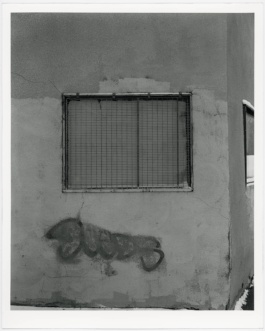

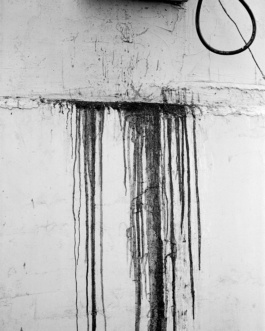

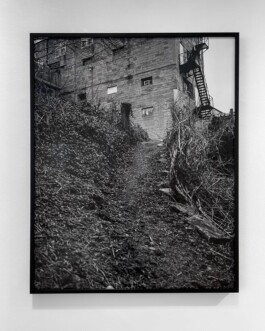

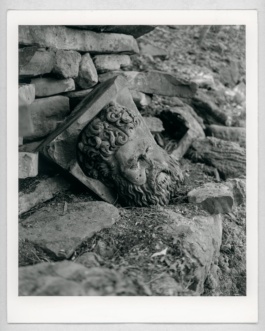

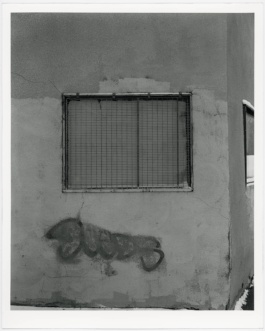

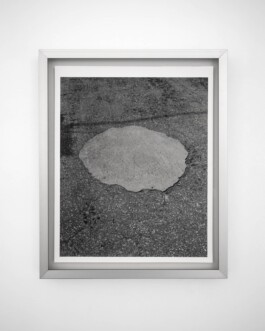

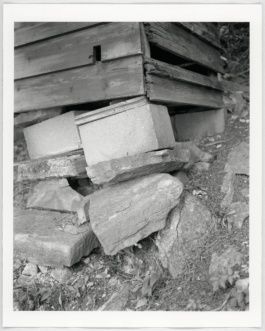

FRECUENCIA (solo show), 2022

Curated by Maria Jose Sagredo.

Installation views, Galería Animal, Santiago de Chile.

Installation photograph © Felipe Ugalde.

Works available with Galería Animal.

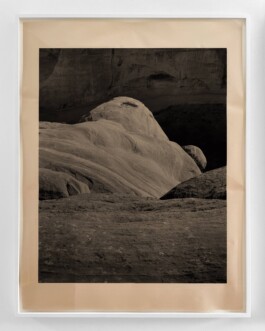

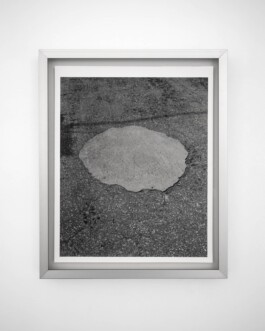

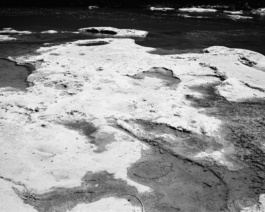

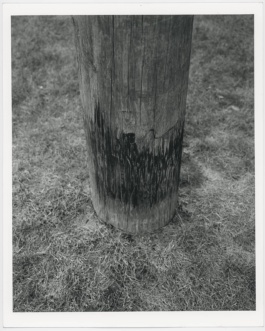

Gelatin silver prints (fiber 255 grs.), Fine art prints (Hahnemühle Rag Baryta 315 grs.). Unique frames (various sizes) on Raulí wood and Nielsen aluminium frames, mounted to archival board with museum glass; Gelatin silver prints and unique Newspaper prints, mounted with Rare-Earth Magnets.

Audio by artist Justin Pape. Composed by improvisational guitar recordings and field recordings in Ontario, Canada. The audio piece was part of the show "Frecuencia" at Galería Animal, Santiago de Chile.

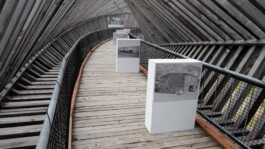

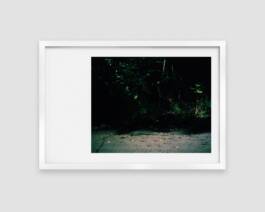

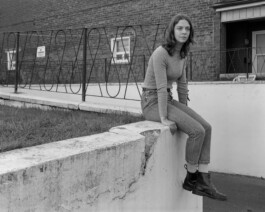

ESPACIO MIGRANTE (group show), 2023

Curated by Anamaría Briede y Catalina de la Cruz

Selected works from Frequency

Museo de la Ciudad, Querétaro, México

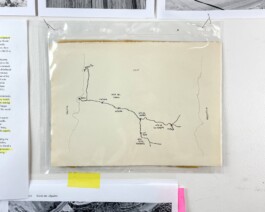

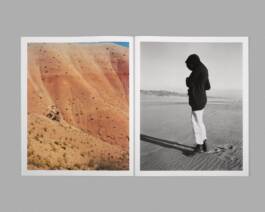

The project takes as its reference - axis - the American territory, specifically South America, and from there it seeks to re-articulate, re-draw and above all re-connect the borders from the photographic practice.

The work is based on the possibility of creating a dialectic that de-configures the notions of territory, identity and geography from the South American perspective that unites us, to inhabit and materialize the poetic illusion of a new imaginary, as a cartography of particular experiences, historical, social, political and emotional contexts. A collaborative visual writing as a repository of mental, intimate, public, emotional images as a glossary of territorial geolocations that indicate the cultural plurality of America.

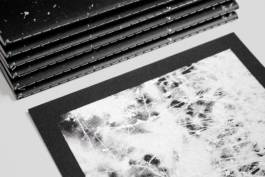

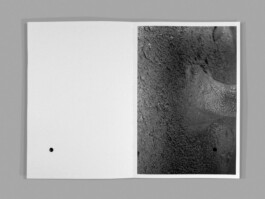

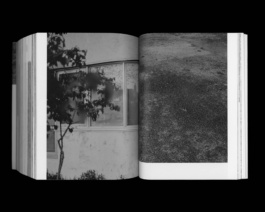

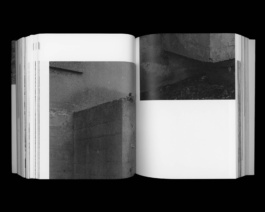

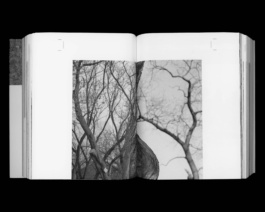

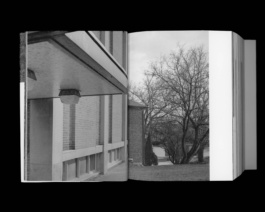

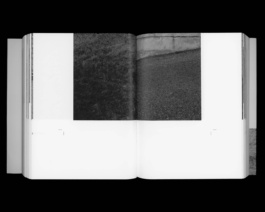

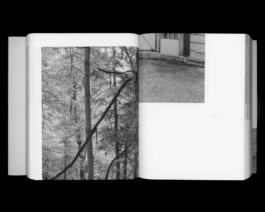

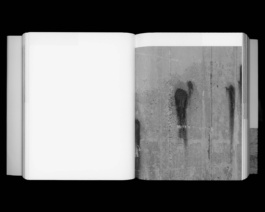

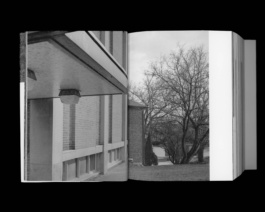

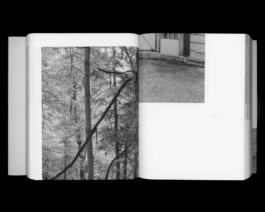

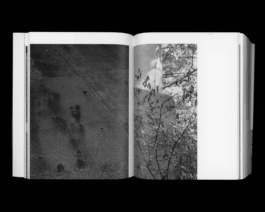

Frequency, B-Sides (Set of 3)

Intended to waste as little as possible, these three publications are a photo/graphic and editorial exercise using proof sheets from Frequency's printing process. Randomly cropped and edited into three unique b-side books.

5 x 6.75 inches

Over 400 pages each

Uniques

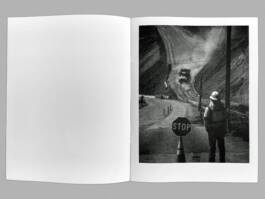

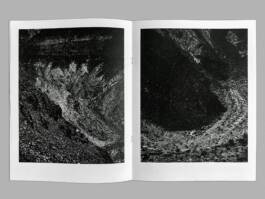

Photopolymer Gravure (diptych), 2021 — Hahnemühle German Etching, 22 x 15.5 inches. Printed in collaboration with print maker Angela Snieder. Unique

COLLECTIONS

2023 — MoMA - Museum of Modern Art, Archives & Library Collection (US)

2023 — NAC - National Gallery of Canada, Library & Archives Collection (CA)

2023 — Library & Archives Canada / Bibliothéque et Archives Canada, Collection (CA)

2023 — AGO - Art Gallery of Ontario, Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives Collection (CA)

2023 — San Telmo Museum, Gabriela Cendoya Bergareche Collection (ES)

2023 — CONTACT Photobook Lab, CONTACT Photography Festival (CA)

AWARDS, GRANTS, HONOURS

2023 — Getxophoto. Pause! Open Call 2023. Shortlisted (ES)

2022 — Canada Council for the Arts. Travel Grant. Arts Abroad program (CA)

2022 — Leica Oskar Barnack Award 2022, Nominee (GE)

2022 — Ontario Art Council. Exhibition Assistance Grant 2021-2022 (CA)

2021 — The Burtynsky Grant. Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. Winner (CA)

2021 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2020. Representations of Space, Architecture, and Conflicts. Winner (IT)

EXHIBITIONS, TALKS, FAIRS

2023 — Photobook Exhibition and Panel Talk (group show) Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (CA)

2023 — CONTACT Photobook Fair. Stephen Bulger Gallery (CA)

2023 — Espacio Migrante (group show). Museo de la Ciudad, Santiago de Querétaro (MX)

2022 — Frecuencia (solo show), Galería Animal (CL)

2022 — Salon 44 (group show), Gallery 44 (CA)

2021 — Latin American Galleries Now. Galería Animal + Artsy (US)

PRESS, REVIEWS

2024 — The Urbanaut Podcast (IT)

2023 — Ciel variable, Photobook Review by Louis Perreault (CA)

2023 — Palm Studios. Featured work (UK)

2022 — Frecuencia, Artishock Magazine. Article by Alejandra Villasmil (CL)

2022 — FotoNostrum Magazine, Issue 23. Feature Article (ES)

2021 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2020. Book (IT)

FRECUENCIA (solo show), 2022

Curated by Maria Jose Sagredo.

Installation views, Galería Animal, Santiago de Chile.

Installation photograph © Felipe Ugalde.

Works available with Galería Animal.

Gelatin silver prints (fiber 255 grs.), Fine art prints (Hahnemühle Rag Baryta 315 grs.). Unique frames (various sizes) on Raulí wood and Nielsen aluminium frames, mounted to archival board with museum glass; Gelatin silver prints and unique Newspaper prints, mounted with Rare-Earth Magnets.

Audio by artist Justin Pape. Composed by improvisational guitar recordings and field recordings in Ontario, Canada. The audio piece was part of the show "Frecuencia" at Galería Animal, Santiago de Chile.

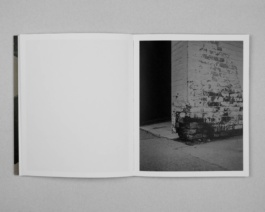

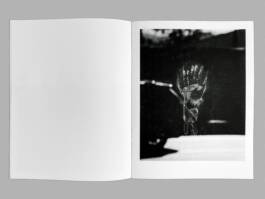

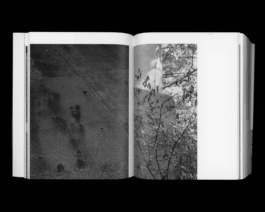

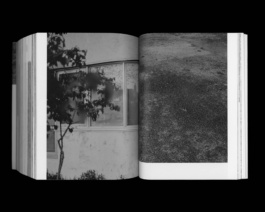

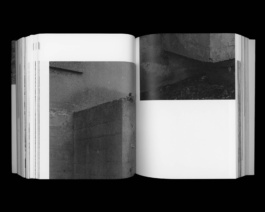

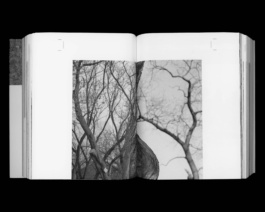

Frequency, B-Sides (Set of 3)

Intended to waste as little as possible, these three publications are a photo/graphic and editorial exercise using proof sheets from Frequency's printing process. Randomly cropped and edited into three unique b-side books.

5 x 6.75 inches

Over 400 pages each

Uniques

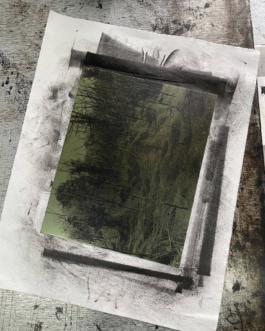

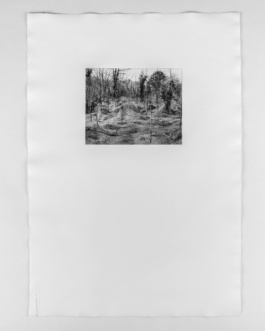

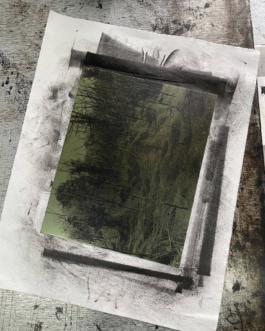

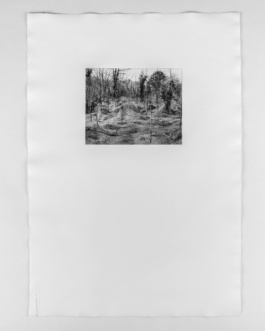

Photopolymer Gravure (diptych), 2021 — Hahnemühle German Etching, 22 x 15.5 inches. Printed in collaboration with print maker Angela Snieder. Unique

COLLECTIONS

2023 — MoMA - Museum of Modern Art, Archives & Library Collection (US)

2023 — NAC - National Gallery of Canada, Library & Archives Collection (CA)

2023 — Library & Archives Canada / Bibliothéque et Archives Canada, Collection (CA)

2023 — AGO - Art Gallery of Ontario, Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives Collection (CA)

2023 — San Telmo Museum, Gabriela Cendoya Bergareche Collection (ES)

2023 — CONTACT Photobook Lab, CONTACT Photography Festival (CA)

AWARDS, GRANTS, HONOURS

2023 — Getxophoto. Pause! Open Call 2023. Shortlisted (ES)

2022 — Canada Council for the Arts. Travel Grant. Arts Abroad program (CA)

2022 — Leica Oskar Barnack Award 2022, Nominee (GE)

2022 — Ontario Art Council. Exhibition Assistance Grant 2021-2022 (CA)

2021 — The Burtynsky Grant. Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. Winner (CA)

2021 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2020. Representations of Space, Architecture, and Conflicts. Winner (IT)

EXHIBITIONS, TALKS, FAIRS

2023 — Photobook Exhibition and Panel Talk (group show) Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (CA)

2023 — CONTACT Photobook Fair. Stephen Bulger Gallery (CA)

2023 — Espacio Migrante (group show). Museo de la Ciudad, Santiago de Querétaro (MX)

2022 — Frecuencia (solo show), Galería Animal (CL)

2022 — Salon 44 (group show), Gallery 44 (CA)

2021 — Latin American Galleries Now. Galería Animal + Artsy (US)

PRESS, REVIEWS

2024 — The Urbanaut Podcast (IT)

2023 — Ciel variable, Photobook Review by Louis Perreault (CA)

2023 — Palm Studios. Featured work (UK)

2022 — Frecuencia, Artishock Magazine. Article by Alejandra Villasmil (CL)

2022 — FotoNostrum Magazine, Issue 23. Feature Article (ES)

2021 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2020. Book (IT)