1 20

FREQUENCY, 2020-22

3 20

4 20

6 20

8 20

10 20

12 20

15 20

17 20

20 20

FREQUENCY, 2020-22

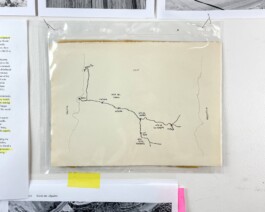

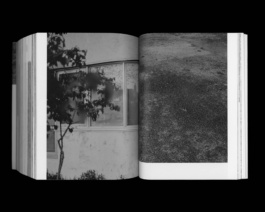

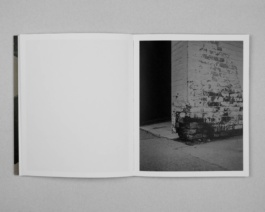

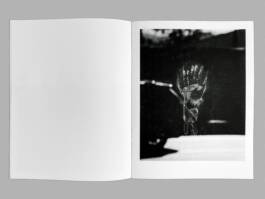

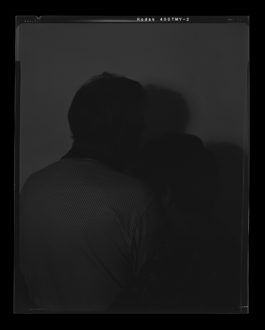

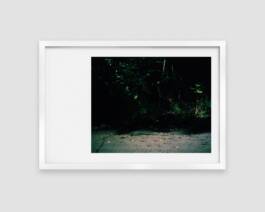

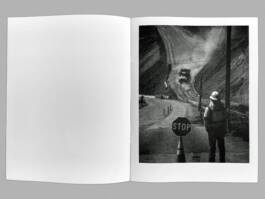

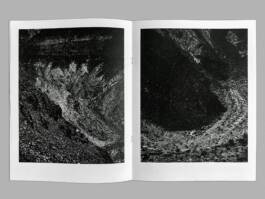

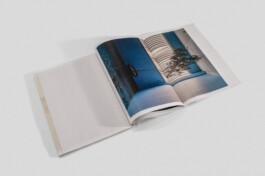

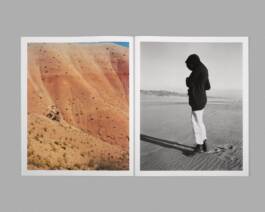

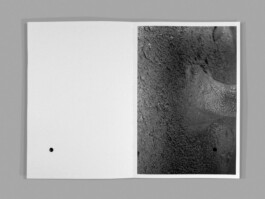

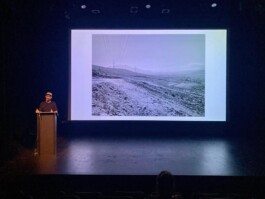

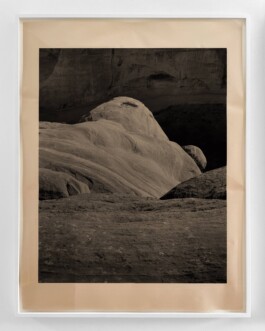

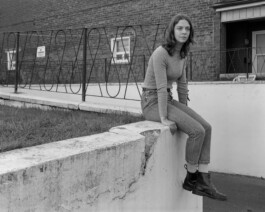

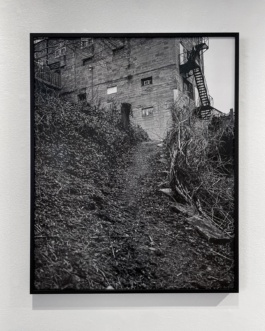

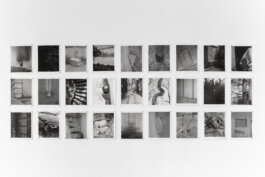

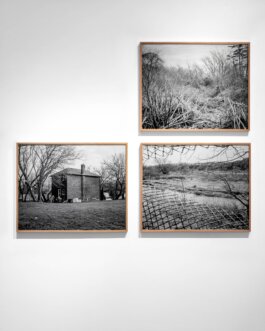

The photographic series Frequency, like an epiphany, provokes me the revelation of the tension and the conflict over the desire to build a custom habitable world, for and by human beings. Cities seem to concentrate the satisfaction of each of our needs, needs without limits that we do not know where they begin and where they end, are revealed as indistinguishable from the desire itself that wanders from the shelter of a building with great heights, from light to energies, from walking to highways, from creating to spectacle, from health care to assisted prolongation of life. A kind of parallel world created especially for humanity as if it were a duality in opposition to the voluptuous and dark world of foliage that could devour us, full of dangers and mysteries of nature. And between it and the human world appear the patches, the marks from the cracks and wounds of streets and buildings that cannot regenerate themselves, heal itself like the forest does, no matter how hard you try. Cement patches and the bricks are the scars of the cities, the hidden frailties of this desire to control and the construction of a safe, complete, self-referring, and sanitized world.

It is the year 2020 and the conflict of this desire with its artificial duality has come to light. The streets, backyards, empty entrances, walls and dead ends are images of loneliness that makes it uncomfortable to express the absence of our presence. At times the ominous has taken the place of that absence, fills it, and we perceive it everywhere without being able to name it. It is on the tip of the tongue and in every vision, as when we observe these photographs. Anguish -that unspeakable and formless feeling that ran underground under the city patches keeping us safe from conflict- its felt in the isolated wandering, like a cold stream in black and white that stops us from looking with more attention and without escape to that daily environment that has become insecure and unknown.

text by Mónica Salinero Rates, Sociologist

audio by Justin Pape, Artist

HIGHLIGHTS:

Getxophoto. Pause! Open Call 2023. Shortlisted. (ES)

Canada Council for the Arts. Travel Grant. Arts Abroad program 2022 (CA)

Leica Oskar Barnack Award 2022, Nominee (GE)

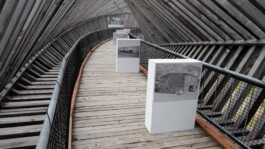

Galería Animal. (Solo Show) Exhibition. 2022 (CL)

Frecuencia, Artishock Magazine. Article by Alejandra Villasmil. 2022 (CL)

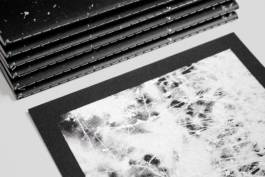

Extempore. Published by Colony Collapse (CA)

Ontario Art Council. Exhibition Assistance Grant 2021-2022 (CA)

The Burtynsky Grant + Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. Winner 2021 (CA)

Urbanautica Institute Awards 2020. Representations of Space, Architecture, and Conflicts. Winner 2021 (IT)

FREQUENCY, 2020-22

FREQUENCY, 2020-22

The photographic series Frequency, like an epiphany, provokes me the revelation of the tension and the conflict over the desire to build a custom habitable world, for and by human beings. Cities seem to concentrate the satisfaction of each of our needs, needs without limits that we do not know where they begin and where they end, are revealed as indistinguishable from the desire itself that wanders from the shelter of a building with great heights, from light to energies, from walking to highways, from creating to spectacle, from health care to assisted prolongation of life. A kind of parallel world created especially for humanity as if it were a duality in opposition to the voluptuous and dark world of foliage that could devour us, full of dangers and mysteries of nature. And between it and the human world appear the patches, the marks from the cracks and wounds of streets and buildings that cannot regenerate themselves, heal itself like the forest does, no matter how hard you try. Cement patches and the bricks are the scars of the cities, the hidden frailties of this desire to control and the construction of a safe, complete, self-referring, and sanitized world.

It is the year 2020 and the conflict of this desire with its artificial duality has come to light. The streets, backyards, empty entrances, walls and dead ends are images of loneliness that makes it uncomfortable to express the absence of our presence. At times the ominous has taken the place of that absence, fills it, and we perceive it everywhere without being able to name it. It is on the tip of the tongue and in every vision, as when we observe these photographs. Anguish -that unspeakable and formless feeling that ran underground under the city patches keeping us safe from conflict- its felt in the isolated wandering, like a cold stream in black and white that stops us from looking with more attention and without escape to that daily environment that has become insecure and unknown.

text by Mónica Salinero Rates, Sociologist

audio by Justin Pape, Artist

HIGHLIGHTS:

Getxophoto. Pause! Open Call 2023. Shortlisted. (ES)

Canada Council for the Arts. Travel Grant. Arts Abroad program 2022 (CA)

Leica Oskar Barnack Award 2022, Nominee (GE)

Galería Animal. (Solo Show) Exhibition. 2022 (CL)

Frecuencia, Artishock Magazine. Article by Alejandra Villasmil. 2022 (CL)

Extempore. Published by Colony Collapse (CA)

Ontario Art Council. Exhibition Assistance Grant 2021-2022 (CA)

The Burtynsky Grant + Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. Winner 2021 (CA)

Urbanautica Institute Awards 2020. Representations of Space, Architecture, and Conflicts. Winner 2021 (IT)