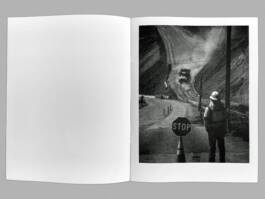

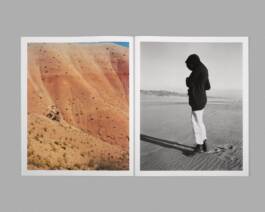

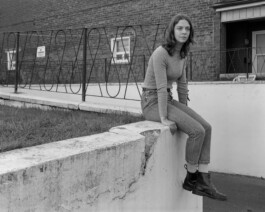

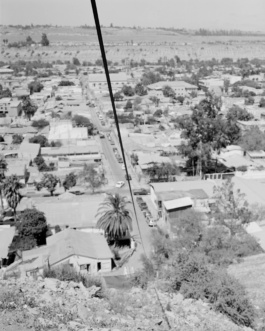

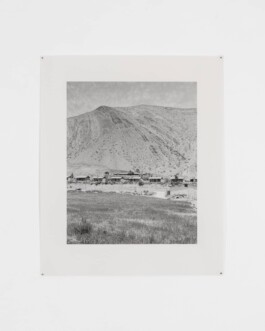

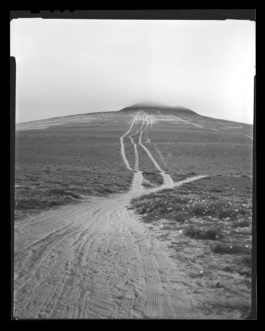

VALLE, 2022-ongoing

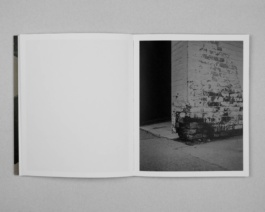

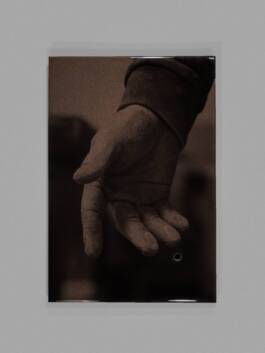

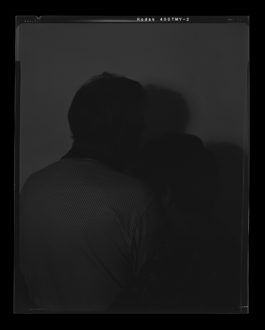

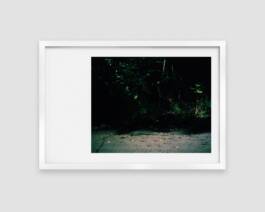

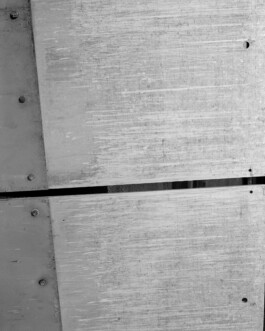

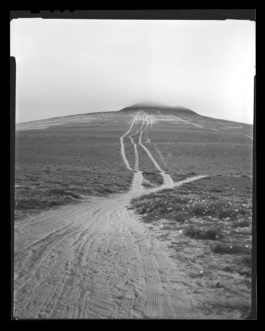

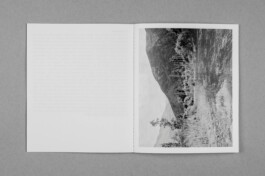

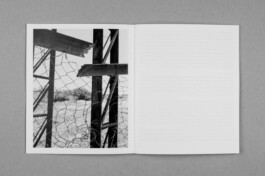

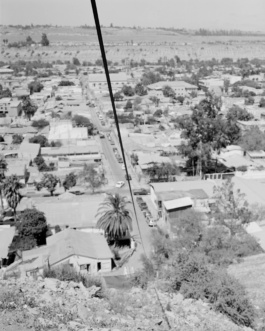

Valle was created as part of a research project in collaboration with Associate Professor, Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce, from Athabasca University (Canada). These photographs are part of a larger body of work that focuses on communities and their territories throughout the Huasco Valley, located in the southern Atacama Desert, Chile. Huasco is the last active valley before the world's driest desert begins, and a place which has been dealing with a variety of environmental, economic and health concerns for more than 30 years. The pictures reflect on concerns that have affected and continue to affect (for better or worse, depending on how you look at it) the life of the communities, the access to basic and universal services, the relationship with what development and the environment mean and represent in the use of this territory.

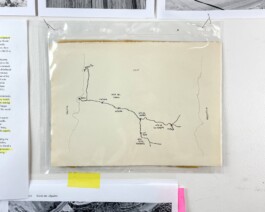

Route taken through the Huasco Valley accompanying the research team in a process of interviews and surveys throughout specific locations in the valley. These photographs are a record with a subjective perspective that was inspired by the studied data, the conversations with the locals, the beauty of the landscape, and human intervention in the territory as it has evolved over time.

—

Read Essay by Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce, PhD

Associate Professor, Athabasca University

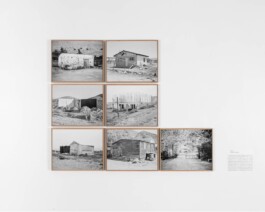

Paisaje común (group show), 2024

Galería Animal, Santiago de Chile.

May 30 to July 13, 2024

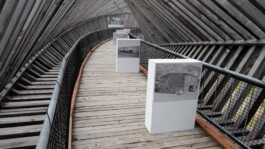

Work part of ‘Valle’ on display at ‘Paisaje Común’, a group exhibition and dialogue with my dear colleagues Javier Aravena, Sebastián Mejía, Cristóbal Palma and Marcos Zegers.

Download Dossier of exhibition (PDF available in Spanish).

Installation photography © Sebastián Mejía and Cristóbal Palma

VALLE (solo public installation), 2023

Photographys by Cristian Ordóñez

Curated by Claude Goulet

Text by Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce

Installation views, 18 photographs. Belvédère des Deux-Rivières, Matapédia (view of the confluence of the Matapédia and Ristigouche rivers), Gaspésie, Québec.

Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (14th edition, 2023)

July 15 to September 30, 2023

A Sense of Place (group show), 2023

Curated by Bénédicte Blondeau and Rüdiger Lange

PEP - Photographic Exploration Project

April 1 - 29, 2023

Berlin, Germany

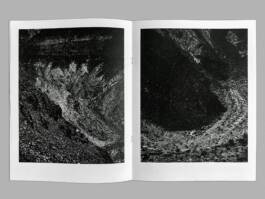

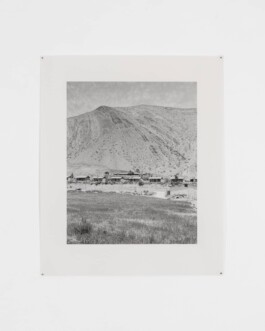

Cerro Centinela (diptych), Atacama, 2022

Oripeau Public Exhibition n°576, Montréal, QC Canada

MULTINACIONALES Y COMUNIDADES: Justicia Socioambiental, Licencia Social para Operar y Desarrollo Comunitario (Proyecto de Investigación)

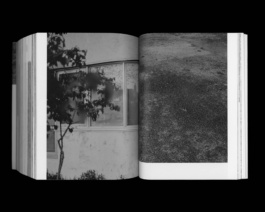

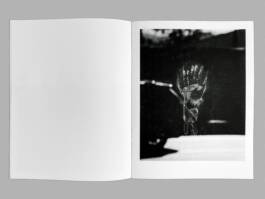

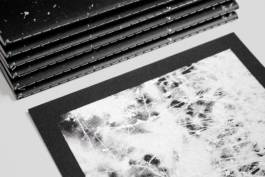

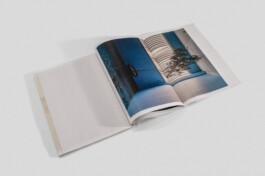

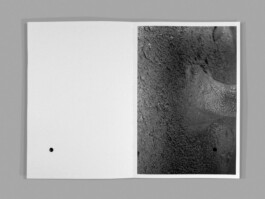

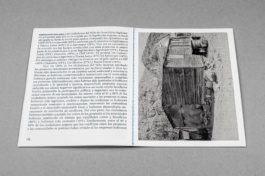

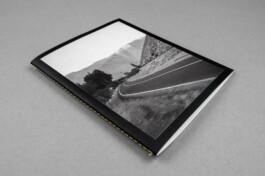

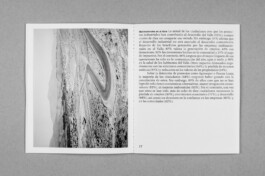

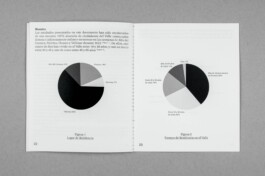

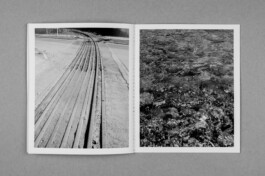

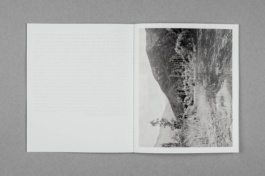

Publication created in response to ongoing research that began in early 2022, including a visit to the Huasco Valley in Atacama, Chile in October of the same year. This book was specially produced in a limited edition to deliver the preliminary quantitative results to the community of Huasco, namely actors from the civil society, the public sector, indigenous peoples, business people and ordinary citizens who participated in this process.

Funded by Athabasca University and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development of the Government of Canada, in collaboration with the Department of Industrial Engineering of the University of Santiago de Chile. Created and edited by Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce, PhD, Athabasca University and Photographer, Cristian Ordóñez.

Self-Published

36 pages

10 Photographs and 7 Pie charts figures

Softcover, tip-on photograph Saddle Sewn binding (2 stitch colours in honour of the colours of the Atacama flag)

Spanish

Free distribution

© 2023

AWARDS

2023 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2022. Nature, Environment and Perspectives. Winner (IT)

EXHIBITIONS, TALKS

2024 — Paisaje Común (group show). Galería Animal (CL)

2024 — Oripeau Public Exhibition n°576, Montréal (CA)

2023 — Valle (solo show). Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (CA)

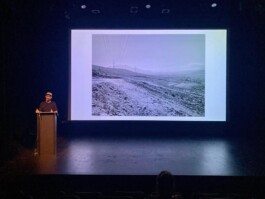

2023 — Valle (artist talk). Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (CA)

2023 — A Sense of Place (group show). PEP - Photographic Exploration Project. Berlin (GE)

PUBLICATIONS

2024 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2022. Book (IT)

2023 — Multinacionales y Comunidades. Self-Published (CA)

PRESS

2025 — Lampoon Magazine, Feature Article (IT)

2025 — LUR. Feature Interview (ES)

2024 — Maisonneuve Magazine, Issue 91. Feature Article (CA)

2024 — The Urbanaut Podcast (IT)

DOWNLOAD

2024 — Paisaje Común Exhibition, Dossier ESP (CL)

VALLE, 2022-ongoing

Valle was created as part of a research project in collaboration with Associate Professor, Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce, from Athabasca University (Canada). These photographs are part of a larger body of work that focuses on communities and their territories throughout the Huasco Valley, located in the southern Atacama Desert, Chile. Huasco is the last active valley before the world's driest desert begins, and a place which has been dealing with a variety of environmental, economic and health concerns for more than 30 years. The pictures reflect on concerns that have affected and continue to affect (for better or worse, depending on how you look at it) the life of the communities, the access to basic and universal services, the relationship with what development and the environment mean and represent in the use of this territory.

Route taken through the Huasco Valley accompanying the research team in a process of interviews and surveys throughout specific locations in the valley. These photographs are a record with a subjective perspective that was inspired by the studied data, the conversations with the locals, the beauty of the landscape, and human intervention in the territory as it has evolved over time.

—

Read Essay by Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce, PhD

Associate Professor, Athabasca University

Paisaje común (group show), 2024

Galería Animal, Santiago de Chile.

May 30 to July 13, 2024

Work part of ‘Valle’ on display at ‘Paisaje Común’, a group exhibition and dialogue with my dear colleagues Javier Aravena, Sebastián Mejía, Cristóbal Palma and Marcos Zegers.

VALLE (solo public installation), 2023

Photographys by Cristian Ordóñez

Curated by Claude Goulet

Text by Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce

Installation views, 18 photographs. Belvédère des Deux-Rivières, Matapédia (view of the confluence of the Matapédia and Ristigouche rivers), Gaspésie, Québec.

Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (14th edition, 2023)

July 15 to September 30, 2023

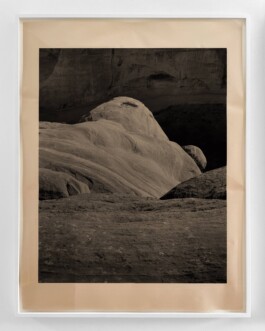

Cerro Centinela (diptych), Atacama, 2022

Oripeau Public Exhibition n°576, Montréal, QC Canada

AWARDS

2023 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2022. Nature, Environment and Perspectives. Winner (IT)

EXHIBITIONS, TALKS

2024 — Paisaje Común (group show). Galería Animal (CL)

2024 — Oripeau Public Exhibition n°576, Montréal (CA)

2023 — Valle (solo show). Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (CA)

2023 — Valle (artist talk). Rencontres de la photographie en Gaspésie (CA)

2023 — A Sense of Place (group show). PEP - Photographic Exploration Project. Berlin (GE)

PUBLICATIONS

2024 — Urbanautica Institute Awards 2022. Book (IT)

2023 — Multinacionales y Comunidades. Self-Published (CA)

PRESS

2025 — Lampoon Magazine, Feature Article (IT)

2025 — LUR. Feature Interview (ES)

2024 — Maisonneuve Magazine, Issue 91. Feature Article (CA)

2024 — The Urbanaut Podcast (IT)

DOWNLOAD

2024 — Paisaje Común Exhibition, Dossier ESP (CL)